Sun-Earth Day 2007 presents: Living in the Atmosphere of the Sun

Heated plasma and magnetic fields can create beautiful details.

ISSUE #53: SOLAR PROMINENCES

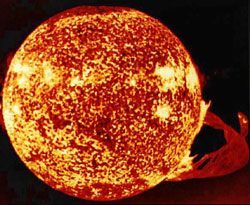

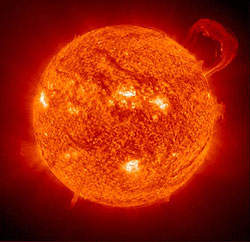

Since the earliest sightings of total solar eclipses, small smudges of red light have been sighted near the dark limb of the eclipses sun. Glowing with the light of hydrogen heated to more than 10,000 C, these 'prominences' of gas were later found to be magnetic arches in which trapped gases glowed.

Charged particles in heated plasmas flow along lines of magnetic force and illuminate them, much the same way that iron filings can be used to trace the delicate loops of magnetism surrounding a toy magnet. Solar physicists still do not understand exactly how the gases enter and leave solar prominences, but the basic details of prominences seem to be pretty well understood after more than 100 years of telescopic and mathematical study.

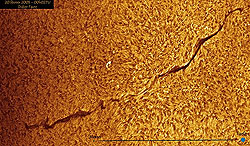

Solar prominences can be as small as a sunspot, about the size of Earth, or extend to nearly the diameter of the sun itself. They can contain 10 to 100 billion tons of heated plasma, extending far into the corona of the sun. Although the surrounding gases in the corona can be up to 1 million degrees hot, prominence gases can be far cooler, and this is one of the puzzles of their origins that physicists are still trying to understand. Because they contain cool gas, when seen from directly above, they appear dark against the hot solar surface just like sunspots! Prominences are called filaments when seen in this way.

Although the cool gases within the prominence itself may not be hot enough to emit x-rays, it is often the case that at the two foot points of the prominence near the solar surface, copious amounts of hot gases may exist. It is thought that the random movement of the prominence magnetic field lines near the foot points is what triggers the heating of the gases there, and that as these gases flow up the prominence, they emit x-ray and ultraviolet radiation and become cooler.

Once formed, as a loop of magnetism leaves the solar surface, prominences can remain stationary or 'quiescent' in space for many hours or days until they suddenly become unstable and erupt. The gases magnetically trapped within these erupting prominences can be hurled out into space as coronal mass ejections. Prominences can become unstable especially when new magnetic field loops are formed beneath them and move upwards, colliding with them from below. Under some circumstances, these collisions can trigger solar flares as opposing magnetic field polarities merge and annihilate, releasing powerful blasts of electromagnetic energy. Under some conditions, the trapped gasses can be heated to nearly 50 million C; far hotter than the interior of the sun itself!

Figure 3: A prominence can appear dark against the brighter solar surface and is then called a filament.

The gas motions in prominences are complex. At the atomic scale, individual charged particles 'orbit' along a magnetic line of force in a spiral motion. The particles may bounce from end to end along the field line, reversing their direction. At larger scales, we see plasma flowing at speeds of up to 50 km/sec along every part of a prominence, but because prominences have very finely scaled magnetic fields, these plasmas are often seen moving in opposite directions; a phenomenon called counter-streaming. Along the sides of quiescent prominences, you can find groups of magnetic threads called 'barbs' along which plasmas are flowing to and from the neighboring chromospheric gases. Physicists think that mass flows along these barbs is what supplies gases from the chromosphere to the prominence arcade. Sometimes, this motion becomes accelerated and the prominences has become 'activated'. Activations can be caused when small flares at one foot point of the prominence inject plasma into the magnetic field lines that pass through the prominence. Only some of these activation events actually lead to an eruption of the prominence.

Technology Through Time

2007 ISSUES

- #57: The Heliosphere

- #56: Coronal Mass Ejections

- #55: Solar Corona, Holes and Wind

- #54: Solar Flares... Oh my!

- #53: Solar Prominences

- #52: Sunspots from A to B - solar magnetism

- #51: The Transit of Mercury

- #50: Ancient Sunlight

- #49: Solar Energy

- #48: The Sun: From Cradle to Grave

View past issues

Authors and Designers

Space Weather Fact

The fastest coronal mass ejection was recorded on August 4, 1972 and traveled from the sun to earth in 14.6 hours - a speed of nearly 10 million kilometers per hour!